Energy Communities and Integration into the Electricity Market

Energy communities explained from a market perspective: how they integrate into real scheduling, aggregation, and balancing mechanisms, the role of suppliers, BRPs, and aggregators, and why operational discipline is essential for power system stability.

1 – Introduction

Energy Communities and Their Integration into the Electricity Market

From a European Concept to Operational Implementation

Energy communities are one of the instruments promoted at European level to accelerate the energy transition, increase consumer participation, and stimulate local energy production from renewable sources. Under the European legislative framework, they are recognized as entities capable of producing, consuming, storing, and sharing energy, with the primary objective of delivering economic, social, and environmental benefits to their members and to the local community.

In Romania, the introduction of the energy community concept has generated an intense debate, focused mainly on the role of the regulatory authority and the level of control exercised over these entities. Unfortunately, much of this debate has taken place in a predominantly political or emotional register, with limited focus on the essential operational aspects of how the energy system actually functions.

Electricity is a product subject to strict physical and operational constraints. Production and consumption must be balanced in real time, and any actor participating in this process—regardless of size or purpose—affects system stability and costs. For this reason, energy communities cannot be analyzed solely as civic or social initiatives; they must be understood as market actors, integrated into a complex mechanism of scheduling, balancing, and settlement.

The purpose of this article is to clarify, in a technical and structured manner:

- how the electricity market functions;

- what role energy communities play within this framework;

- why their integration must be carried out through aggregation and balancing mechanisms;

- what adaptations are required in terms of processes, systems, and regulation so that these communities can operate efficiently and predictably.

The proposed approach does not challenge the need for energy communities. Rather, it argues that their success depends on aligning with the physical and operational realities of the energy system, not on opposing them.

2 – Roles, Responsibilities, and Balancing Mechanisms

To correctly understand the place of energy communities, a brief but rigorous overview is needed of how the electricity market functions. This is not a classic goods market, but a real-time coordinated system in which each participant has clear obligations, and failure to meet them generates immediate costs.

2.1. The Fundamental Principle: Production–Consumption Balance

Electricity cannot be stored in the grid. At every moment, production must equal consumption. Any deviation from this balance affects system frequency and requires rapid interventions to maintain stability.

For this reason, the energy market is built around the concepts of:

- scheduling (what energy is expected to be produced and consumed),

- balancing (correcting deviations from the schedule),

- financial responsibility for the deviations generated.

This framework applies to all actors, regardless of size or legal form.

2.2. OPCOM – Price Formation and Commercial Commitments

OPCOM operates the centralized electricity markets, where prices and traded volumes are established for various time horizons (day-ahead markets, intraday markets, bilateral contracts).

Transactions executed on these markets represent:

- firm commercial commitments;

- quantities of energy that must be delivered or consumed according to the resulting schedules.

OPCOM does not manage the physical delivery of energy, but provides the framework through which actors assume obligations that are subsequently integrated into the balancing system.

2.3. Suppliers – The Interface with Final Consumers

Suppliers are the actors who purchase energy from the market and sell it to final consumers. Beyond the contractual relationship with the customer, suppliers have essential operational responsibilities:

- forecasting the consumption of their customer portfolio;

- transmitting these forecasts to the balancing responsible party (BRP);

- settling the differences between forecast and actual consumption.

The final consumer is not directly visible in balancing mechanisms; responsibility is assumed by the supplier and its associated BRP (PRE).

2.4. BRP (PRE) – Responsibility for Imbalances

The balancing responsible party (PRE) is the entity that assumes and manages the risk of imbalances generated by its portfolio (suppliers, producers, aggregators).

The PRE:

- aggregates the schedules of all participants in its portfolio;

- manages the differences between scheduled and actual energy;

- bears the costs of imbalances according to balancing market rules.

The more volatile and less predictable a portfolio is, the higher the balancing costs.

2.5. Distribution System Operators – The Physical Infrastructure

Distribution system operators manage the low- and medium-voltage networks and are responsible for:

- connecting consumers and producers to the grid;

- metering energy;

- supply quality and safety.

They do not participate in commercial transactions, but they provide the metering data that forms the basis for settlement and balancing.

2.6. Transelectrica – Balancing the National Power System

Transelectrica, as the transmission system operator, has the role of maintaining the production–consumption balance at national level in real time. When imbalances cannot be compensated within BRP (PRE) portfolios, Transelectrica activates system reserves.

The costs of these interventions are real and are subsequently redistributed within the system through balancing tariffs.

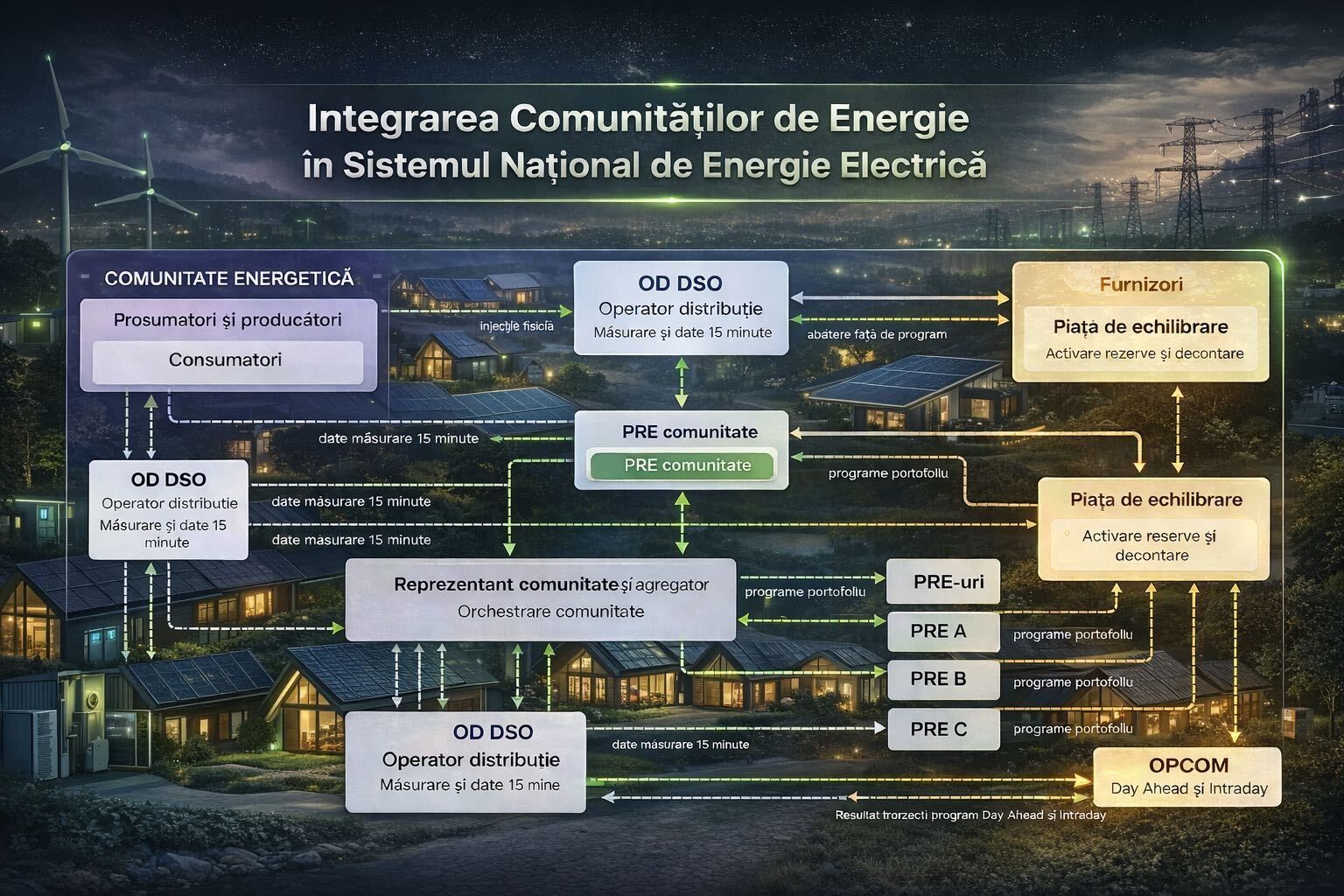

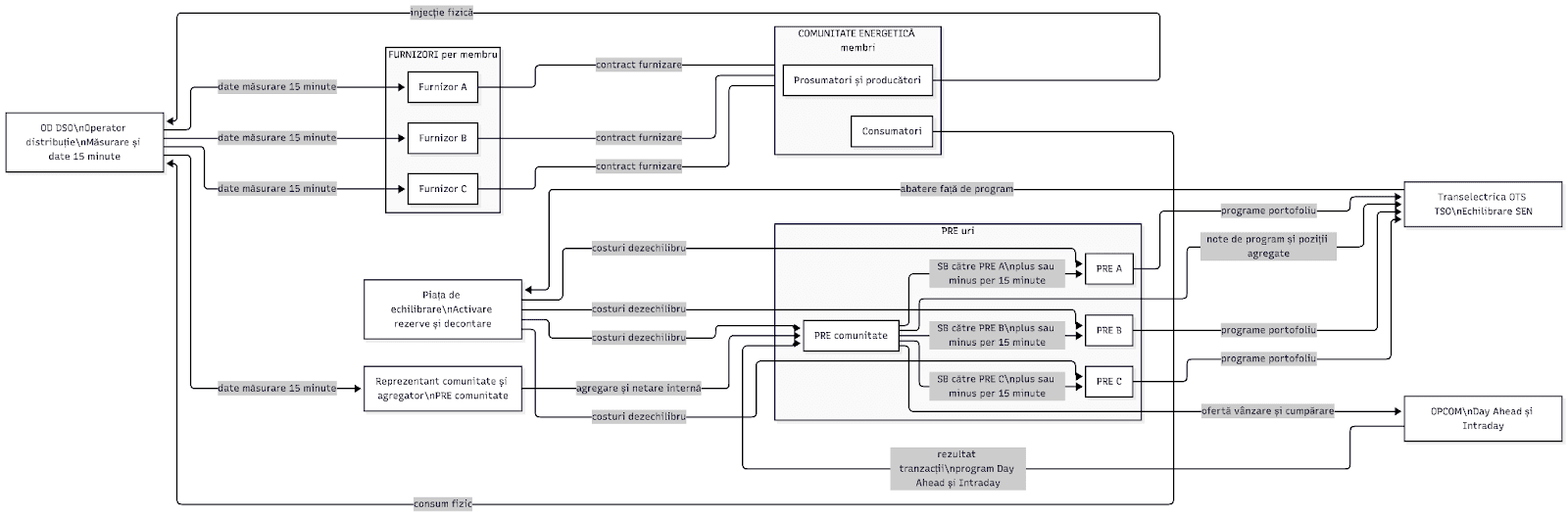

Functional relationship between actors

The standard operational flow is as follows:

- suppliers and aggregators submit consumption and production schedules to the BRP;

- BRPs aggregate these schedules and submit them to Transelectrica;

- Transelectrica operates the NES based on the received schedules;

- deviations between scheduled and realized energy generate imbalances;

- imbalances are settled through the balancing market mechanisms.

This chain operates on the basis of aggregation and assumed responsibility, not at the level of individual consumers.

The electricity market is an interdependent system built on scheduling, aggregation, and the assumption of responsibility for imbalances. Once integrated into the NES, energy communities cannot operate outside these mechanisms. They must be treated as aggregated market actors—integrated through suppliers, aggregators, and BRPs—so that they contribute to system stability rather than increasing imbalances.

3 – Energy Communities in the Electricity Market

Two operational models: internal compensation and active market participation

In practice, an energy community becomes relevant only when it can be integrated into the real mechanisms of the market: scheduling, balancing, and settlement. For this reason, the discussion should not be carried out only in legal terms (“the community exists”), but in operational terms (“how the community behaves in the market, what it submits, who is responsible for imbalances, who bears the costs, and how double counting is avoided”).

A key aspect is that community members retain the freedom to choose their supplier. As a result, a single community may include multiple suppliers, and each supplier is linked to a different Balancing Responsible Party (BRP / PRE). Therefore, the community cannot be treated as a simple consumer or a simple producer. It becomes an aggregated structure that requires a coordination mechanism. This mechanism is ensured through a mandated party (an aggregator or supplier) operating through a community-dedicated BRP (hereafter BRP_CE / PRE_CE).

Depending on the maturity level of the community and of the mandated party, there are two main operating modes.

3.1. The energy community as an internal compensation mechanism

“Passive” model: the community reduces billed consumption and reconciles positions with suppliers

In the passive model, the energy community is used primarily as an internal compensation mechanism: members’ production is used with priority to cover members’ consumption, and any differences (surplus or deficit) are reconciled correctly vis-à-vis each member’s supplier. The community does not “replace” suppliers, does not assume the supplier role, and does not require a parallel market; it merely reduces the energy that suppliers must purchase from the market—provided that data is transmitted correctly so that the National Energy System (NES / SEN) is not burdened with artificial imbalances.

The key point of this model is that community members may have different suppliers. Each supplier has its own BRP (PRE). In addition, the community is operated by a mandated party (aggregator/supplier) that works through a community BRP (PRE_CE). To avoid accounting errors, PRE_CE must generate block exchanges (SB) broken down by supplier, so that each supplier knows exactly how much consumption to remove from billing and/or how much export to recognize in its portfolio.

Example 1 – Production surplus in the community (SB EXPORT to suppliers’ BRPs)

Assume a community with two suppliers:

- PRE_1 – Supplier E.ON: Members 1, 2, 3

- PRE_2 – Supplier Hidroelectrica: Members 4, 5, 6

- PRE_CE: The community BRP (mandated party / aggregator)

Within a 15-minute interval, measured values are:

- M1 (E.ON) produces 10 kWh

- M2 (E.ON) produces 23 kWh

- M3 (E.ON) consumes 30 kWh

- M4 (Hidro) consumes 10 kWh

- M5 (Hidro) produces 100 kWh

- M6 (Hidro) produces 100 kWh

At community level:

- total production = 10 + 23 + 100 + 100 = 233 kWh

- total consumption = 30 + 10 = 40 kWh

- community surplus = 193 kWh

In the passive model, the community covers internal consumption first, then the surplus must be recognized correctly by suppliers (not left “unassigned”). Breakdown by supplier groups:

- E.ON group: production 33 kWh, consumption 30 kWh → +3 kWh surplus

- Hidro group: production 200 kWh, consumption 10 kWh → +190 kWh surplus

Therefore, PRE_CE submits export block exchanges:

- to PRE_1 (E.ON): SB_EON = +3 kWh

- to PRE_2 (Hidro): SB_HIDRO = +190 kWh

Effect: each supplier BRP adjusts its portfolio correctly, and Transelectrica sees the real export—rather than “unscheduled production” or artificial imbalances.

Example 2 – Production deficit in the community (SB IMPORT after proportional redistribution)

Now assume that in another 15-minute interval the community has consumption far higher than production:

- M1 (E.ON): produces 10 kWh, consumes 20 kWh

- M2 (E.ON): produces 23 kWh, consumes 40 kWh

- M3 (E.ON): produces 0 kWh, consumes 30 kWh

- M4 (Hidro): produces 0 kWh, consumes 50 kWh

- M5 (Hidro): produces 20 kWh, consumes 80 kWh

- M6 (Hidro): produces 10 kWh, consumes 60 kWh

Community aggregate:

- total production = 10 + 23 + 20 + 10 = 63 kWh

- total consumption = 20 + 40 + 30 + 50 + 80 + 60 = 280 kWh

- community deficit = 217 kWh

In such a situation, the available production (63 kWh) must be redistributed proportionally to consumers based on each one’s share of total consumption. In other words, each member receives a portion of the community’s production proportional to their consumption, and the remainder becomes residual consumption that must be covered by the supplier.

After proportional redistribution, the total residual consumption is 217 kWh, which must be transferred to suppliers (by groups) through import block exchanges. After aggregation by supplier (illustrative, based on redistribution calculations), we obtain:

- E.ON group: residual consumption 69.75 kWh

- Hidro group: residual consumption 147.25 kWh

Therefore, PRE_CE submits import block exchanges:

- to PRE_1 (E.ON): SB_EON = −69.75 kWh

- to PRE_2 (Hidro): SB_HIDRO = −147.25 kWh

Effect: suppliers cover the residual consumption from the market, and the NES receives coherent net positions. The community does not generate artificial imbalances because any consumption not covered internally is explicitly taken over by suppliers through their BRPs.

3.2. The energy community active in the market

“Advanced” model: the mandated party (aggregator) monetizes surplus in the Day-Ahead and Intraday markets via PRE_CE

In the active model, the energy community does not limit itself to internal compensation; it can become a relevant economic actor by monetizing its production surplus in centralized markets (Day-Ahead and Intraday) through its mandated party (aggregator/supplier) operating via the community BRP (PRE_CE).

The difference from the passive model is not about “rights,” but about operational capability. To sell energy in the market, the community must be able to forecast production and consumption, build firm schedules, and manage deviations from the schedule without transferring uncontrolled costs to the NES. In other words, an active community must behave like a responsible portfolio, not as a source of unassigned volatility.

In all cases, the fundamental rule remains the same: internal consumption is covered first, and only the surplus (if any) becomes available for sale.

3.2.1. Example 1 – Day-Ahead sale of the community surplus (scheduling one day ahead)

Assume the community’s aggregator (via PRE_CE) produces a forecast for the following day (D+1). The community has the following aggregated estimates:

- forecast production for D+1: 1,200 kWh

- forecast consumption of members: 700 kWh

- forecast surplus available for market: 500 kWh

In this scenario, the mandated party:

- confirms that internal needs (700 kWh) are covered with priority from community production;

- determines marketable surplus: 500 kWh;

- submits a Day-Ahead sell offer for 500 kWh according to strategy (hourly/quarter-hour profile);

- after market closure, obtains a firm accepted schedule for delivering those 500 kWh.

At this point, the energy is no longer a “hypothetical surplus.” It becomes a scheduled delivery obligation of PRE_CE in the market. From the NES perspective, it is scheduled energy, not accidental injection.

Impact on members and their suppliers:

- members’ suppliers remain responsible for any residual consumption (if any);

- the community manages export via PRE_CE;

- block exchanges to suppliers’ BRPs still apply for internal compensation (netting), but the surplus destined for the market is managed separately by PRE_CE.

3.2.2. Example 2 – Intraday adjustment to reduce imbalances (forecast vs actual difference)

Assume that on the delivery day (D+1) conditions differ from the forecast (e.g., higher solar irradiance). The community’s actual production becomes:

- actual production: 1,260 kWh

- actual consumption: 700 kWh (kept constant for clarity)

- actual surplus: 560 kWh

But in Day-Ahead, the community scheduled a sale of 500 kWh. This creates a difference of:

- surplus versus schedule: +60 kWh

Without correction, this 60 kWh becomes a deviation and may generate balancing costs. In the active model, the aggregator uses the Intraday market to correct the position:

- submits an additional Intraday sell offer for 60 kWh;

- if accepted, aligns the schedule with actual delivery;

- reduces or eliminates the deviation.

Conclusion: Intraday is the tool through which an active community minimizes imbalances and associated costs before they reach the balancing market.

3.2.3. Example 3 – Negative case: production below the Day-Ahead schedule (need to buy / reduce position)

Assume the opposite scenario: unfavorable weather reduces actual production:

- actual production: 1,100 kWh

- actual consumption: 700 kWh

- actual surplus: 400 kWh

But the community sold 500 kWh in Day-Ahead. This creates a deficit versus schedule of:

- delivery shortfall: −100 kWh

In this case, the community (through the aggregator) has two correct operational options:

- buy 100 kWh in Intraday to cover the delivery obligation; or

- partially close/reduce the position through permitted market mechanisms (depending on applicable rules).

If no correction is made, the 100 kWh remains a deviation and enters balancing, generating costs.

This is why active communities need:

- good forecasting;

- Intraday trading capability;

- automation and digital processes.

3.2.4. Relationship with members’ suppliers and block exchanges in the active model

The active model does not eliminate the SB mechanism described in the passive model. On the contrary, it becomes even more important because two components run simultaneously:

- internal component (member-to-member compensation): handled through block exchanges sent to suppliers’ BRPs, broken down by supplier-member groups;

- external component (surplus sold to market): handled directly by PRE_CE in Day-Ahead/Intraday.

In short:

- energy used for internal compensation is reflected in block exchanges to suppliers’ BRPs;

- energy remaining as surplus after compensation is scheduled and sold by PRE_CE.

Thus, suppliers are not “removed from the equation”; they receive correct net positions for their members, while the community monetizes surplus without polluting the NES with accounting-driven deviations.

An active energy community is entirely feasible, but it requires operational discipline: forecasting, scheduling, and adjustment. Its major advantage is that the community’s surplus is not just passively injected—it becomes transparently traded energy, generating revenues and improving system efficiency. At the same time, integration still depends on correct reconciliation through block exchanges to suppliers’ BRPs, so that the NES receives coherent schedules and clean net positions.

4 – Scheduling, Forecasting, and Balancing

Why “scheduling notes” and reconciliation before the NES are mandatory

If Section 3 explains who the actors are and which block exchanges must circulate between BRPs (PREs), this section explains why the system requires scheduling and how imbalance costs are avoided when energy communities (passive or active) appear.

Electricity is delivered and consumed in real time, but the market operates on the basis of commitments made in advance: each portfolio (through its BRP / PRE) must communicate to the system operator an expected profile of injections and withdrawals. This profile is the “schedule” or “scheduling note.” When actual values differ from the schedule, the difference becomes an imbalance and is settled according to balancing market rules.

In the case of energy communities, the major risk is not the existence of prosumers, but the fact that—without a rigorous scheduling and reconciliation mechanism—local variations end up being treated as unassigned deviations at the level of the National Energy System (NES / SEN). The more numerous and volatile communities become (especially PV-based ones), the more structural this problem becomes.

4.1. What the community forecast is, and why it must be done on short intervals

An energy community aggregates consumers and producers. Therefore, forecasting must cover two components:

- production forecasting (typically weather-dependent, for PV/wind);

- consumption forecasting (dependent on behavior, temperature, day/holiday patterns, etc.).

In a modern system, the operationally relevant forecast is the one built on settlement intervals (e.g., 15 minutes), because:

- real energy exchanges are recorded and settled per interval;

- deviations occur on short intervals (not “as a monthly average”);

- remedial adjustments (Intraday / balancing) only make sense if there is sufficient granularity.

From a practical perspective, the community forecast does not need to be “perfect.” It must be good enough to:

- enable reasonable scheduling towards the TSO;

- enable Intraday corrections before balancing;

- reduce systematic deviations.

4.2. Scheduling notes: who submits them and how they reach Transelectrica

The correct chain (functionally) is:

- Members → metering (DSO) → aggregation (mandated party) → PRE_CE

- PRE_CE generates schedules/positions and integrates them into its portfolio

- The PRE (including PRE_CE) submits aggregated schedules to the TSO

- The TSO operates the NES based on schedules and activates reserves for deviations

In a passive community, the PRE_CE schedule mainly reflects:

- the aggregated profile of injections and withdrawals (after internal compensation), and

- the block exchanges sent to suppliers’ PREs (which adjust those suppliers’ portfolios).

In an active community, the PRE_CE schedule additionally includes:

- commercial positions from Day-Ahead and Intraday (sell/buy), and

- adjustments made to reduce deviations versus actual outcomes.

Important: block exchanges are not “administrative details.” They are precisely the mechanism that keeps suppliers’ schedules correct after part of the consumption has been covered inside the community or after part of the surplus has been allocated/sold.

4.3. What happens if block exchanges and schedules are not properly reconciled

If PRE_CE does not transmit block exchanges (SB) to suppliers’ PREs (or if they are not integrated correctly), three typical effects occur:

- Double-counted consumption

The supplier continues to schedule and bill consumption that, in reality, was partially covered by the community’s production. - “Unscheduled” production

The community’s injection appears in the system without being coherently reflected in schedules, therefore entering as a deviation. - Artificial imbalance in the NES

The TSO is forced to compensate through reserves what is, in fact, a data and reconciliation inconsistency—not a physical lack of energy.

These artificial imbalances increase balancing costs and penalize actors who, physically, may have operated correctly but communicated incompletely or inconsistently.

4.4. Numerical example: a simple deviation and Intraday correction (active community)

Assume PRE_CE sold a Day-Ahead surplus of 500 kWh for day D+1, for a relevant aggregated interval.

On day D+1, actual values indicate:

- production is +60 kWh above forecast (actual surplus 560 kWh).

If PRE_CE does nothing, the +60 kWh becomes a deviation and enters balancing.

If PRE_CE is active and has Intraday capability, it executes:

- an Intraday sell transaction for 60 kWh, aligning the schedule with actual delivery.

The result is that the imbalance is reduced to near zero (within system limits), which:

- lowers balancing costs;

- reduces the need to activate reserves;

- increases system stability.

The same logic applies in reverse (when production is below schedule): PRE_CE buys in Intraday or reduces the position before balancing.

4.5. The need to update TSO mechanisms for automated exchanges (including DAMAS)

As energy communities become more numerous, manual management of block exchanges and reconciliations becomes unsustainable. Therefore, at system level an evolution is needed towards:

- automated intake of block exchanges between PREs;

- integration into standard scheduling and reconciliation flows;

- validation and traceability (audit) of exchanges.

Without such automation, the likelihood increases that:

- an SB is submitted late or incompletely;

- a supplier does not adjust its schedule in time;

- the deviation reaches the NES as an imbalance.

Therefore, a “registry-only” regulation for communities is not sufficient; an operational integration regulation into the scheduling–balancing chain is also required.

Energy communities become sustainable and scalable only if they are integrated into scheduling and balancing mechanisms through a coherent chain of forecasting, scheduling notes, and timely block exchanges. A community that cannot produce these elements is not “freer”—it simply transfers costs and instability to the NES.

5 – Digital Protocols and Minimum Interoperability Rules

Why the “mirrored” SB mechanism blocks aggregation and flexibility, and what must be changed in DAMAS

The integration of energy communities and distributed energy resources (DER) does not stop at defining the actors and correctly calculating netting. In practice, the main bottleneck appears at the point where these positions must become operationally accepted within the TSO’s systems. Here a critical issue emerges: the current mechanism for accepting block exchanges (SB) is built on the premise that an SB is valid only if it is declared “in mirror” by both involved parties.

In other words, Transelectrica does not effectively accept an SB submitted unilaterally by a BRP (PRE). Instead, it treats it as valid only if:

- the BRP that “sends” declares the SB with one sign, and

- the “receiving” BRP declares the same SB with the opposite sign,

and the two declarations match perfectly (volume, interval, identifiers).

This rule may appear reasonable in a system with few actors and rare flows. In a market with aggregators, energy communities, and distributed flexibility, it becomes a structural blocking mechanism.

5.1. The problem: the SB becomes dependent on the other party’s consent

In the energy community and flexibility model, the community BRP (PRE_CE) or the aggregator’s BRP must be able to submit SBs to suppliers’ BRPs so that:

- consumption is correctly removed from suppliers’ portfolios,

- production is correctly allocated,

- the National Energy System (NES / SEN) does not see artificial imbalances.

However, if an SB is accepted only under the “mirrored declaration” condition, then the supplier’s BRP gains an operational veto in practice: if it does not declare the SB (or declares it differently), the SB is not accepted in the system.

This means that the aggregator—although theoretically an independent actor—becomes indirectly obstructed by the supplier through the supplier’s BRP. Aggregation independence becomes formal rather than real.

5.2. Direct effect: DER flexibility and aggregation cannot scale

Flexibility services require fast response, granularity, and the ability for an aggregator to operate over a portfolio whose members may have different suppliers. If every aggregator action (or every SB) requires symmetric confirmation from suppliers’ BRPs, then:

- the process cannot be automated;

- reaction times become incompatible with real flexibility;

- delays and administrative disputes emerge;

- innovation is effectively “frozen”: technically possible, operationally not accepted.

The consequence is profound: not only energy communities are affected, but the entire direction of integrating DER into the NES.

5.3. Why this mechanism generates today’s implementation problems

This is, in essence, the structural problem that explains why many “distributed resources” initiatives collide with reality: not because technology is missing, but because there is no operational acceptance mechanism that works in a multi-actor system.

When the TSO conditions acceptance of an SB on a “double signature” (mirrored entry), the system operates as a blocking mechanism, not as a market mechanism. In a functional market, a BRP should be treated as a responsible, compliant actor—not as a participant able to unilaterally block operational transactions simply through inaction.

5.4. Principle proposal: automatic acceptance of a “presumed valid” SB, with later reconciliation

For aggregation and flexibility to work, DAMAS (and its associated operational flows) must be updated so that:

- SBs can be automatically accepted at system level even if the mirrored declaration is not yet present;

- the SB is treated as “provisionally valid” based on the responsibility of the BRP that submits it;

- any dispute is handled later, within a data-driven reconciliation stage.

This is a “trust-first, verify-later” operational model, conceptually similar to consistency and reconciliation mechanisms in distributed systems: flows are not blocked at entry just because the counterparty confirmation is missing; they are processed, and disputes are resolved later based on evidence.

5.5. Concrete DAMAS mechanism proposal: acceptance + objection window + reconciliation

A realistic model, compatible with modern markets, could work as follows:

Phase 1: SB submission by the initiating BRP (PRE_CE / aggregator)

The SB is automatically ingested by the TSO system and recorded under a unique identifier.

Phase 2: Provisional application in schedules / positions

The SB is used in net position calculations so that the NES is not burdened with artificial imbalances.

Phase 3: Formal objection window for the “receiving” BRP

The receiving BRP may:

- explicitly accept (ideal), or

- submit a reasoned objection supported by evidence (metering data, inconsistency, identification error, etc.).

Phase 4: Reconciliation and settlement

If a valid objection exists, a reconciliation process is triggered, in which:

- net positions and actual imbalances are recalculated,

- corrections and related settlements are applied.

Key point: objections must be evidence-based, not “through inaction.” Inaction must not block the market.

5.6. Major benefit: removal of the indirect veto right and unlocking the flexibility market

With this update, the aggregator stops being dependent on the supplier. The supplier remains a relevant actor, but can no longer implicitly block flexibility mechanisms simply by not declaring the mirrored SB.

This is the step without which:

- distributed flexibility cannot be implemented at scale;

- energy communities cannot function stably in the market;

- network optimization remains theoretical.

The major problem is not the existence of energy communities, but the current SB acceptance architecture based on mandatory mirrored confirmation. In a modern system, this rule blocks aggregation and flexibility because it grants a third-party BRP an implicit veto over the aggregator’s operations.

DAMAS must be updated to allow automatic acceptance of SBs submitted by a BRP, with the option for later, reasoned dispute and data-based reconciliation. Without this change, integrating distributed resources into the NES will remain structurally limited, and the flexibility market will not function effectively.

6 – Concrete recommendations for regulation and implementation

A realistic framework for communities, aggregation, and flexibility, without operational bottlenecks

After clarifying the operating models, the need for scheduling and balancing, and the interoperability bottlenecks, it becomes possible to formulate concrete recommendations. The objective of this section is not to create bureaucracy, but to define minimum, verifiable, and automatable rules that allow energy communities to operate correctly in the market and contribute to grid optimization.

6.1. Recommendations for ANRE – regulation oriented toward functioning, not only toward registry

ANRE should explicitly define the minimum operational rules that make it possible to integrate communities without artificial imbalances. Concretely, it is necessary to have:

- defining the role of the mandated party (aggregator/supplier) and its operational responsibilities;

- recognizing the community’s BRP (PRE_CE) as the orchestrator of internal compensation and of SBs toward suppliers’ BRPs;

- defining an implicit deficit redistribution rule (proportional to consumption per interval), auditable and automatable;

- requiring SBs split by supplier, not only aggregated “at community level”;

- explicitly separating operational SB (prevention) from reconciliation SB (post-factum, including within the window accepted by the TSO).

6.2. Recommendations for Transelectrica (TSO) – modernization of DAMAS and elimination of the indirect “veto right”

It is necessary to update DAMAS so that acceptance of SBs does not depend rigidly on mirrored confirmation from both BRPs. The recommendation is:

- automatic (provisional) acceptance of SBs initiated by a BRP, with traceability and a unique identifier;

- a formal objection window, in which the challenge must be reasoned and supported by data;

- subsequent reconciliation, including imbalance recalculation where non-compliance is proven.

This change is the practical condition for independent aggregation and for flexibility services that function at scale.

6.3. Recommendations for DSOs – granular metering and standardized digital access

DSOs must ensure metering available at the settlement-interval resolution and standardized digital access for authorized actors, with unique identifiers and traceability. Without this, reconciliation becomes arbitrary and contestable.

6.4. Recommendations for suppliers and BRPs – digital integration and the obligation of operational cooperation

Suppliers and BRPs must have the obligation to digitally integrate received SBs (Ack/Nack and error management), as well as the obligation not to obstruct the functioning of aggregation through inaction, especially in a model where DAMAS accepts SB provisionally.

6.5. Recommendations for aggregators (PRE_CE) – operational discipline and transparency

Aggregators must demonstrate:

- correct and reproducible calculation of internal compensation for each interval;

- supplier-split SB generation, transmitted digitally and auditable;

- for the active model: forecasting, Intraday trading, and reduction of deviations versus schedule;

- transparency toward members regarding methodology and results.

6.6. Phased implementation

A gradual introduction is recommended:

- Phase 1: passive communities – internal compensation + supplier-split SB + standard format;

- Phase 2: active communities – Day-Ahead/Intraday + forecasting + imbalance reduction;

- Phase 3: distributed flexibility – provisional SB acceptance in DAMAS + subsequent reconciliation.

Încheiere

Comunitățile de energie nu sunt un „hack” împotriva pieței și nici o excepție de la regulile SEN. Ele pot funcționa corect și pot aduce beneficii reale – facturi mai mici, investiții locale, autonomie parțială și, pe termen mediu, flexibilitate distribuită – doar dacă sunt integrate disciplinat în mecanismele existente de programare, echilibrare și decontare.

Disputa publică devine inutilă când ignoră realitatea tehnică: energia nu se poate „partaja” doar prin declarații și registre. În spatele fiecărui kWh există măsurare, programare, responsabilitate de echilibrare și costuri reale dacă datele nu sunt reconciliate. De aceea, comunitățile nu pot fi lăsate să opereze într-o zonă nereglementată, dar nici sufocate prin birocrație care nu rezolvă nimic. Soluția realistă este una singură: reguli minime, digitale, auditabile, care permit interoperabilitatea între toți actorii.

Punctul critic pentru viitor nu este doar comunitatea, ci agregarea și flexibilitatea. Dacă schimburile block rămân condiționate de confirmarea „în oglindă” din partea ambelor PRE-uri, agregatorul rămâne blocat indirect de furnizor, iar flexibilitatea distribuită devine imposibilă la scară. De aceea, modernizarea DAMAS și a regulilor de acceptare a SB-urilor – cu acceptare automată și reconciliere ulterioară pe bază de date – este una dintre cheile reale pentru eficientizarea rețelei și pentru integrarea DER în România.

În final, comunitățile de energie pot deveni o soluție „win-win” doar dacă fiecare actor își asumă rolul corect:

- comunitatea și mandatarul calculează și comunică transparent;

- furnizorii și PRE-urile integrează digital și nu obstrucționează;

- OD furnizează măsurare granulară și acces standardizat la date;

- OTS operează pe baza unor mecanisme moderne de acceptare și reconciliere;

- ANRE reglementează funcționarea, nu doar existența.

Asta nu e politică. Este inginerie de sistem și arhitectură de piață. Dacă o facem corect, comunitățile de energie nu vor fi un conflict, ci un accelerator al modernizării energetice.

Conclusion

Energy communities are not a “hack” against the market, nor an exception to the rules of the National Energy System (SEN). They can function correctly and deliver real benefits—lower bills, local investments, partial autonomy, and, in the medium term, distributed flexibility—only if they are disciplinefully integrated into the existing mechanisms of scheduling, balancing, and settlement.

Public debate becomes pointless when it ignores the technical reality: energy cannot be “shared” only through declarations and registries. Behind every kWh there is metering, scheduling, balancing responsibility, and real costs if data is not reconciled. That is why communities cannot be left to operate in an unregulated area, but neither should they be suffocated by bureaucracy that solves nothing. There is only one realistic solution: minimum, digital, auditable rules that enable interoperability among all actors.

The critical point for the future is not only the community, but aggregation and flexibility. If block exchanges remain conditioned by “mirrored” confirmation from both BRPs (PREs), the aggregator remains indirectly blocked by the supplier, and distributed flexibility becomes impossible at scale. For this reason, modernizing DAMAS and the SB acceptance rules—through automatic acceptance and subsequent data-based reconciliation—is one of the real keys to improving network efficiency and integrating DER in Romania.

In the end, energy communities can become a “win-win” solution only if each actor assumes the correct role:

- the community and the mandated party calculate and communicate transparently;

- suppliers and BRPs integrate digitally and do not obstruct;

- DSOs provide granular metering and standardized access to data;

- the TSO operates on the basis of modern acceptance and reconciliation mechanisms;

- ANRE regulates functioning, not only existence.

This is not politics. It is systems engineering and market architecture. If we do it correctly, energy communities will not be a conflict, but an accelerator of energy modernization.

Industrial Renewable Integration Made Simple

Romania’s industry is entering a new energy era. INOWATTIO’s hybrid SCADA–IoT platform connects solar panels, batteries, and industrial consumption into one intelligent system that cuts costs, enhances control, and enables participation in the balancing market. A new standard for efficiency, resilience, and sustainable energy management.

A Simple Guide to Understanding Energy Aggregation

A friendly guide to energy aggregation: how Inowattio pools home solar and batteries so you can lower bills, earn credits, and use energy smarter.

Smart Aggregation and DER Dispatchability for Romania’s Energy Market

INOWATTIO enables the real-time aggregation and dispatch of distributed energy resources (DERs) — solar, batteries, and flexible consumers — into a unified, controllable network. Through intelligent coordination and market integration, decentralized flexibility becomes a stable and valuable asset for Romania’s energy grid.

How to turn Your Home into a Smart Energy Source

Discover how to transform your home into a smart energy ecosystem. The INOWATTIO platform connects your solar panels, batteries, and household devices into one intelligent system that reduces your energy bill, increases efficiency, and brings you closer to energy independence.